Molecular Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration

Research group of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy

We are interested in the molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative disorders, in particular Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We employ a variety of neuropathological, molecular biology and biochemical methods. We further use mouse models of AD to investigate the relationship between learning- and memory deficits and associated pathological alterations in the brain.

Selected current projects

The role of environmental factors in the development of Alzheimer’s disease

Several recent studies investigate the influence of environmental factors such as physical activity or nutritional factors on the course of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in transgenic mouse models. We use the so-called “Enriched Environment” paradigm, providing a stimulating environment due to the presence of running wheels or various toys. We were able to detect that increased physical activity is associated with a considerable improvement in learning and memory performance, an amelioration of neuron loss and an increased neurogenesis rate in these mice (e.g. Hüttenrauch et al., Transl Psych 2016; Gerberding et al., ASN Neuro 2019; Stazi and Wirths, Behav Brain Res 2021). Recently, we were able to show that nutritional factors such as caffeine consumption exert beneficial effects on learning and memory in animal models (Stazi et al., Cell Mol Life Sci 2022; Stazi et al., Eur Arch Psych Clin Neurosci 2023; Stazi et al., Int J Mol Sci 2023).

Selected References:

Gerberding A.-L., Zampar S., Stazi M., Liebetanz D., Wirths O. (2019) Physical activity ameliorates impaired hippocampal neurogenesis in the Tg4-42 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. ASN Neuro, 1759091419892692, https://doi.org/10.1177/1759091419892692

Hüttenrauch M., Brauß A., Kurdakova A., Borgers H., Klinker F., Liebetanz D., Salinas-Riester G., Wiltfang J., Klafki H.W., Wirths, O. (2016) Physical activity delays hippocampal neurodegeneration and rescues memory deficits in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. Translational Psychiatry, 6: e800, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.65

Hüttenrauch M., Salinas G., Wirths O. (2016) Effects of long-term environmental enrichment on anxiety, memory, hippocampal plasticity and overall brain gene expression in C57BL6 mice. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 9:62, http://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2016.00062

Stazi M., Wirths O. (2021) Physical activity and cognitive stimulation ameliorate learning and motor deficits in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioural Brain Research, 397: 112951, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112951

Stazi M., Lehmann S., Sakib M.S., Pena-Centeno T., Büschgens L., Fischer A., Weggen S., Wirths O. (2022) Long-term caffeine treatment of Alzheimer mouse models ameliorates behavioural deficits and neuron loss and promotes cellular and molecular markers of neurogenesis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 79(1): 55 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-021-04062-8

Stazi M., Zampar S., Nadolny M., Büschgens L., Meyer T., Wirths O. (2023) Combined long-term enriched environment and caffeine supplementation improve memory function in C57Bl6 mice. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 273: 269-281, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01431-7

Stazi M., Zampar S., Klafki H.W., Meyer T., Wirths O. (2023) A combination of caffeine supplementation and enriched environment in Alzheimer's disease mouse model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(3): 2155, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032155

Role of N-terminal modified Abeta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease

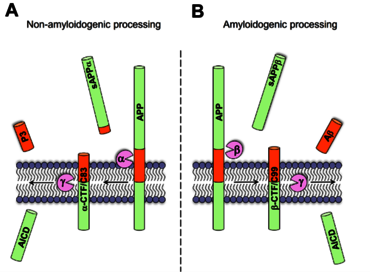

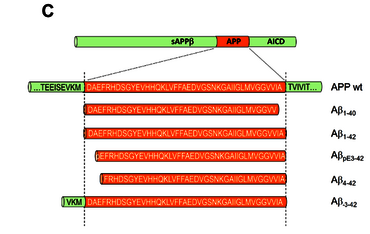

The deposition of so-called amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptides in the form of extracellular plaques is one of the major neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In addition to the full-length Abeta1-40 and Abeta1-42 peptides, which are generated by sequential of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by beta- and gamma-secretase, further N-terminal modified peptide variants have been identified (Wirths and Zampar, Expert Opin Ther Targets 2019). Among these are truncated Abeta peptides starting with the amino acid phenylalanine at position 4 (Abeta4-x), which have been identified in brain samples from AD patients and AD mouse models (Wirths et al., Alzheimers Res Ther 2017; Zampar et al., Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2020; Bader et al., Life 2023), as well as N-terminally elongated (such as Abeta-3-40) (Klafki et al., Int J Mol Sci 2020; Klafki et al., J Neurochem 2022) or post-translationally modified Abeta species (Liepold et al., J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2023; Schrempel et al., Acta Neuropathol 2024). Recently, we identified the metalloprotease ADAMTS4 as an enzyme that is involved in the generation of Abeta4-x peptides as well as of N-terminally elongated Abeta variants (Walter et al., Acta Neuropathol 2019; Wirths et al., Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2024). We are further interested in the potential influence of these modified peptides on myelination and their role in oligodendrocytes (Depp et al., Nature 2023; Sasmita et al., Nat Neurosci 2024) as ADAMTS4 is highly expressed in this particular cell type in the brain.

Fig. 1a: While the enzymatic cleavage by alpha-secretase precludes the formation of Abeta peptides (AD), sequential cleavage by beta- and gamma-secretase results in Abeta formation (B).

Fig. 1b: A variety of Abeta peptides exist that can be modified at the amino- or carboxyterminus (e.g. truncated or elongated) (C).

Selected References:

Bader A.S., Gnädig M.U., Fricke M., Büschgens L., Berger L.J., Klafki H.W., Meyer T., Jahn O., Weggen S., Wirths O. (2023) Brain region-specific differences in amyloid-beta plaque composition in 5XFAD mice. Life, 13: 1053, https://doi.org/10.3390/life13041053

Depp C., Sun T., Sasmita A.O., Spieth L., Berghoff S.A., Nazarenko T., Overhoff K., Steixner-Kumar A.A., Subramanian S., Arinrad S., Ruhwedel T., Möbius W., Göbbels S., Saher G., Werner H.B., Damkou A., Zampar S., Wirths O., Thalmann M., Simons M., Saito T., Saido T., Krueger-Burg D., Kawaguchi R., Willem M., Haass C., Geschwind D., Ehrenreich H., Stassart R., Nave K.-A. (2023) Myelin dysfunction drives amyloid deposition in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature, 613: 349-357, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06120-6

Klafki H.W., Wirths O., Mollenhauer B., Liepold T., Rieper P., Esselmann H., Vogelgsang J., Wiltfang J., Jahn O. (2022) Detection and quantification of Abeta-3-40 (APP669-711) in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of Neurochemistry, 160: 578-589, https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.15571

Klafki H.W., Morgado B., Wirths O., Jahn O., Bauer C., Schuchhardt J., Wiltfang J. (2022) Is plasma amyloid-beta 1-42/1-40 a better biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease than Abeta x-42/x-40? Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 19(1): 96, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-022-00390-4

Liepold T, Klafki H.W., Kumar S., Walter J., Wirths O., Wiltfang J., Jahn O. (2023) Matrix development for the detection of phosphorylated amyloid-beta peptides by MALDI-TOF-MS. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 34(3): 505-512, https://doi.org/10.1021/jasms.2c00270

Sasmita A.O., Depp C., Nazarenko T., Sun T., Siems S.B., Ong E.C., Nkeh Y.B., Boehler C., Yu X., Bues B., Evangelista L., Mao S., Morgado B., Wu Z., Ruhwedel T., Subramanian S., Börensen F., Overhoff K., Spieth L., Berghoff S.A., Sadleir K.R., Vassar R., Eggert S., Goebbels S., Saito T., Saido T., Saher G., Möbius W., Castelo-Branco G., Klafki H.W., Wirths O., Wiltfang J., Jäkel S., Yan R., Nave K.A. (2024) Oligodendrocytes produce amyloid-beta and contribute to plaque formation alongside neurons in Alzheimer’s disease model mice.Nature Neuroscience, 27: 1668-1674, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01730-3

Schrempel S., Kottwitz A.K., Piechotta A., Gnoth K., Büschgens L., Hartlage-Rübsamen M., Morawski M., Schenk M., Kleinschmidt M., Serrano G.E., Beach T.G., Rostagno A., Ghiso J., Heneka M.T., Walter J., Wirths O., Schilling S., Roßner S. (2024) Identification of isoAsp7-Abeta as a major Abeta variant in Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular dementia.Acta Neuropathologica, 148: 78 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-024-02824-9

Walter S., Jumpertz T., Hüttenrauch M., Ogorek I., Gerber H., Storck S.E., Zampar S., Dimitrov M., Lehmann S., Lepka C., Berndt C., Wiltfang J., Becker-Pauly C., Beher D., Pietrzik C.U., Fraering P., Wirths O*. and Weggen S*. (2019) The metalloprotease ADAMTS4 generates N-truncated Abeta4-x peptides and marks oligodendrocytes as a pro-amyloidogenic cell lineage in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica, 137: 239-257 (*corresponding authors), https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1929-5

Wirths O., Lehnen C., Fricke M., Talucci I., Klafki H.-W., Morgado B., Lehmann S., Münch C., Liepold T., Wiltfang J., Rostagno A., Ghiso J., Maric H.M., Jahn O., Weggen S. (2024) Amino-terminally elongated Abeta-3-x peptides are generated by the secreted metalloprotease ADAMTS4 and deposit in a subset of Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neuropathology Applied Neurobiology, 50(3): e12991, https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12991

Wirths O., Walter S., Kraus I., Klafki H.W., Stazi M., Oberstein T., Ghiso J., Wiltfang J., Bayer T.A., Weggen S. (2017) N-truncated Abeta4-x peptides in sporadic Alzheimer's disease cases and transgenic Alzheimer mouse models. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 9(1): 80, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-017-0309-z

Wirths O., Zampar S. (2019) Emerging roles of N- and C-terminally truncated Abeta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 23(12): 991-1004, https://doi.org/10.1080/14728222.2019.1702972

Zampar S., Klafki H.W., Sritharen K, Bayer T.A., Wiltfang J., Rostagno A., Ghiso J., Miles L.A., Wirths O. (2020) N-terminal heterogeneity of parenchymal and vascular amyloid-beta deposits in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology Applied Neurobiology, 46: 273-285, https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12637

Role of signal transduction cascades in inflammatory processes and neurodegenerative diseases

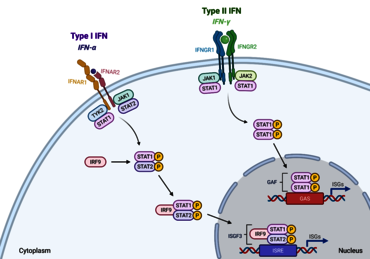

Increasing evidence suggests that neuroinflammation contributes to progression and severity of AD. Activated microglial cells cluster around beta-amyloid deposits and seem to play a role in their clearance via phagocytosis (Hüttenrauch et al., Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018; Aichholzer et al., Alzheimers Res Ther 2021) but also in beta-amyloid deposition (Kaji et al., Immunity 2024). The so-called STAT proteins (signal transducer and activator of transcription) are important transcription factors (Menon et al. BBA – Mol Cell Res 2021; Menon et al., Cell Commun Signal 2022; Remling et al. Cell Commun Signal 2023; Annawald et al., Cell Commun Signal 2025), which might be involved in the pathophysiological changes in inflammatory conditions (Sheik et al., Cell Commun Signal 2025; Annawald et al., Cell Commun Signal 2025) . We aim to investigate the function of these STAT proteins in the context of AD with appropriate transgenic mouse models, with a focus of their specific role in microglial cells (Kaji et al., Immunity 2024; Büschgens et al., Cell Commun Signal 2025).

Fig. 2: Overview of the Jak-STAT signaling pathway. Upon binding of cytokines and growth factors, receptor dimerization leads to JAK recruitment, subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation and STAT docking site formation. Following tyrosine phosphorylation, STATs separate from the receptor and form homo- or heterodimers prior to entering the nucleus and activating transcription of target genes (Büschgens et al., 2025).

Selected References:

Aichholzer F., Klafki H.W., Ogorek I., Vogelgsang J., Wiltfang J., Scherbaum N., Weggen S., Wirths O. (2021) Evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB) as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 13: 94, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00828-1

Annawald K., Gregus A., Wirths O., Meyer T. (2025) Characterization of a pathogenic gain-of-function mutation in the N-terminal domain of STAT1 which is reported to be associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Cell Communication & Signaling, 23: 367, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-025-02330-9

Büschgens L., Hempel N., Methi A., Fischer A., Siering N., Piepkorn L., Jahn O., Meyer T., Wirths O. (2025) Behavioral assessment and gene expression changes in a STAT1 targeted-disruption mouse model. Cell Communication & Signaling, 23: 305 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-025-02313-w

Hüttenrauch M., Ogorek I., Klafki H.W., Otto M., Stadelmann C., Weggen S., Wiltfang J. Wirths O. (2018) Glycoprotein NMB: a novel Alzheimer’s disease associated marker expressed in a subset of activated microglia. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 6(1): 108, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0612-3

Kaji S., Berghoff S.A., Spieth L., Sasmita A.O., Büschgens L., Kedia S., Schlapphoff L., Zirngibl M., Nazarenko T., Damkou A., Vitale S., Hosang L., Depp C., Kamp F., Scholz P., Ewers D., Ischebeck T., Wurst W., Wefers B., Schifferer M., Willem M., Nave K.-A., Haass C., Arzberger T., Jäkel S., Wirths O., Saher G., Simons M. (2024) Apolipoprotein E aggregation in microglia initiates Alzheimer’s disease pathology by seeding beta-amyloidosis. Immunity, 57: 2651-2668, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2024.09.014

Menon P.R., Doudin A., Gregus A., Wirths O., Staab J., Meyer T. (2021) The anti-parallel dimer conformation of STAT3 is required for the inactivation of cytokine signal transduction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Molecular Cell Research, 1868(12): 119118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.119118

Menon P.R., Staab J., Gregus A., Wirths O., Meyer T. (2022) An inhibitory effect on the nuclear import of phospho-STAT1 by its unphosphorylated form. Cell Communication & Signaling, 20(1): 42, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-00841-3

Remling L., Gregus A., Wirths O., Meyer T., Staab J. (2023) A novel interface between the N-terminal and coiled‑coil domain of STAT1 functions in an autoinhibitory manner. Cell Communication & Signaling, 21: 170, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-023-01124-1

Sheikh S.M., Staab J., Bleyer M., Ivetic A., Lüder F., Wirths O., Meyer T (2025) Amino-terminal truncation of STAT1 transcription factor causes CD3- and CD20-negative non-Hodgkin lymphoma through upregulation of STAT3-mediated oncogenic functions.Cell Communication & Signaling, 23: 201, https://doi:10.1186/s12964-025-02183-2

Contact

Research Group Leader

Prof. Dr. Oliver Wirths

+49 551 3965669

e-mail: owirths(at)gwdg.de

Publications: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=wirths-o